Background

In a previous post I’ve discussed how Azure Firewall running in forced tunnel mode doesn’t appear to pass traffic that uses Application Rules to the final target (in this case a Firewall NVA), however following a discussion with Microsoft (thanks Adam Stuart), I now understand how the traffic is presented and how I misunderstood the behaviour.

In a previous post here I described how we saw some unexpected behaviour when passing traffic through the Azure Firewall in Forced Tunnel mode, specifically the below.

When deploying and configuring applications, it was identified that even with traffic flows allowed through Application rules, traffic wasn’t hitting the second firewall NVA as expected. Traffic was seen being processed by the Azure Firewall but the traffic was not getting to the NVA. Traffic directed to Microsoft endpoint URLs that was allowed through a Network rule that used service tags was being passed to the NVA.

A Learning

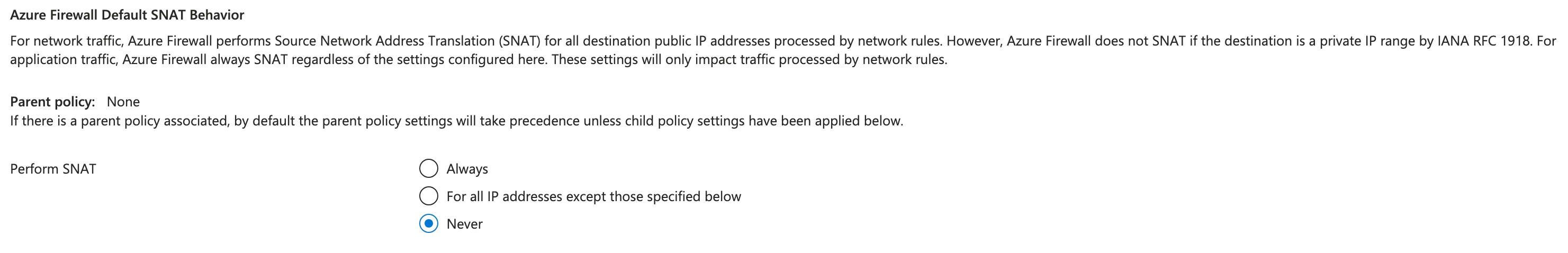

Where I was wrong was how the traffic would be presenting to the Firewall NVA. To allow us to track completely source to target flows in the environment we had configured the Azure Firewall policy to never SNAT any traffic.

This meant that when traffic hit the Firewall NVA we saw the true source address and not the SNAT address of the Azure Firewall.

What I hadn’t fully grasped and I should have done is that this only applies to Network Rules, Application Rules ALWAYS SNAT irrespective of the policy configuration. Microsoft document this behaviour and I completely missed it.

Application rules are always SNATed using a transparent proxy whatever the destination IP address.

A Correction

This meant of course the traffic was hitting our Firewall NVA after all and Application rules do respect the routing configuration but we would see the traffic with the source IP(s) of the Azure Firewall and not of the source device.

We did some checking of the Firewall NVA logs and sure enough we saw traffic hitting the NVA from the firewall IP.

So my previous assumption was completely wrong.

This behaviour suggest that leveraging force tunnel mode prevents the Application rules from working. I suspect this is because internally Azure Firewall expects traffic matching Application rules to egress through it’s own public IP, and it does not expect the traffic to pass through the firewall service. Definitely one to watch out for.

The explanation is much more simple, Applications Rules always SNAT so you always see the source IP of the Azure Firewall and not the Source device.

Architectural Implications

Okay with some humble pie eaten and a much more healthy respect for SNAT, what does this mean architecturally?

Well the reason we needed to dig in to this further was that in the customer scenario, they were looking to deploy a Windows 365 environment with Azure Network Connection (ANC). ANC has a number of specific requirements when it comes to networking ANC Requirements specifically for Azure Firewall it meant using FQDN Tags

Return of the SNAT

FQDN Tags are specific to Application rules, which also means that traffic hitting these rules will SNAT. This is fine, however it does mean that traffic from these devices bound for the internet (or indeed the Microsoft Edge) will not be able to identify the source VM. This may also cause problems if you are sending web browser traffic via the Azure Firewall then you’ll not be able to see the source VM on the Firewall NVA.

Approaches

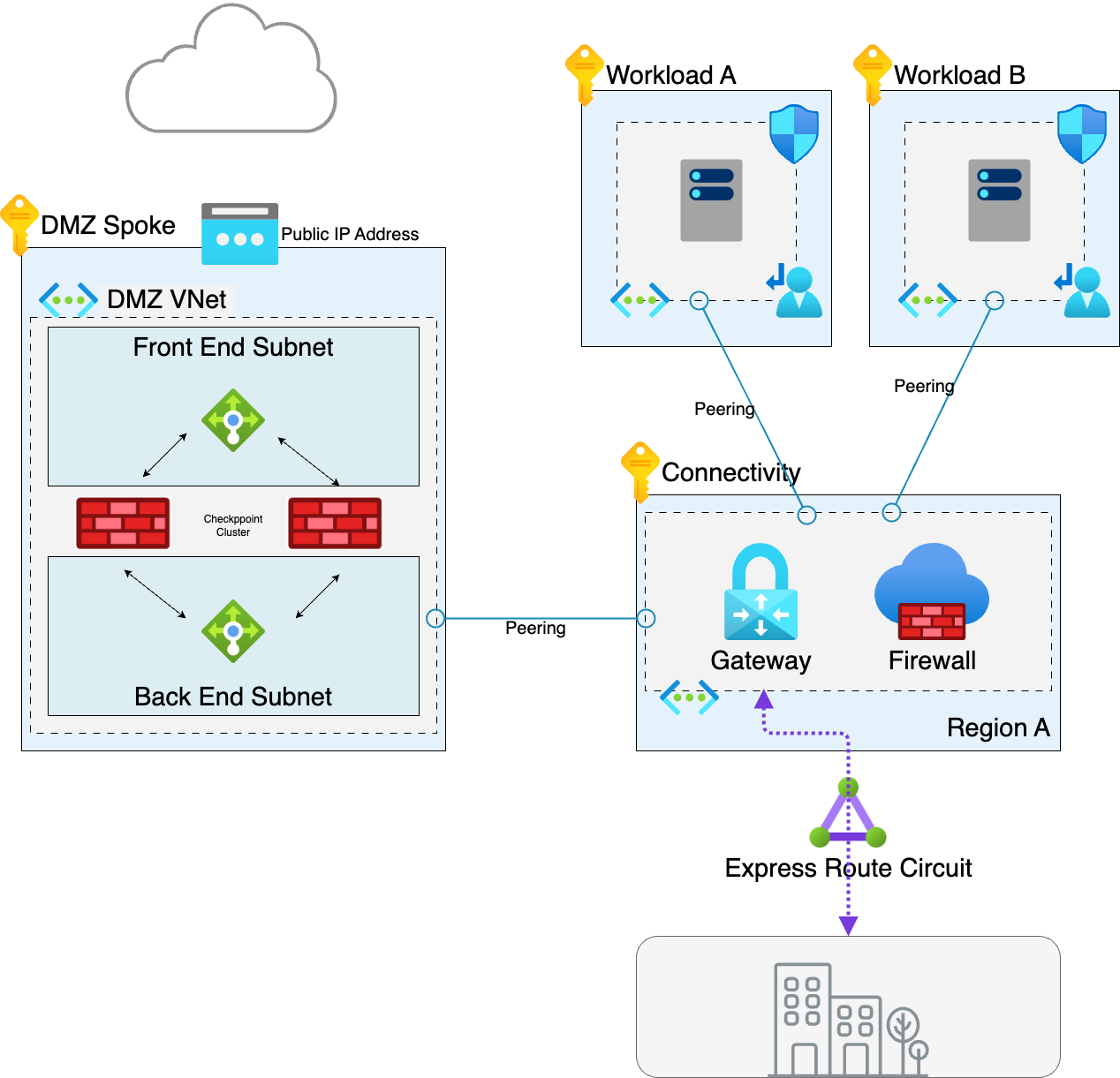

Given the Architecture that has been deployed with the Hub Spoke and DMZ

There are a couple of approaches.

Option 1 - Create a new separate landing zone environment for the Windows 365 ANC deployment

This is a good option in large W365 deployments where you have 000’s of devices which will all be trying to communicate with the internet and the applications. A separate landing zone will allow the user traffic to be segregated from the application traffic.

The reason this may be important to you is that the two types of traffic are very different. Application traffic is pretty well defined and likely to be fairly steady, there will be ramps when through the day when users access the applications but this traffic is likely to be predictable and follow a similar pattern day in day out. User traffic on the other hand is much more random, aside from applications users will be accessing web services, file shares and many other sources of data and traffic, this will be much less predictable and much more random.

Why does this matter, well Azure Firewall is under the hood a set of scale units hidden behind a load balancer. This means as load increases and decreases Azure firewall scales up and down. This scaling is relatively seamless, however some applications do not take kindly to redistribution of traffic and potential TCP resets that may be seen, causing the inevitable flood of tickets to the Service Desk.

So in the event of say the release of Tylor Swift Tickets at 11 am, your W365 users might all decide to hit the Ticketing Website and attempt to source tickets. This will randomly increase the load on the Azure Firewall and potentially cause unplanned disruptions to all users who’s traffic is passing through Azure Firewall, be those traditional thick client users based on the office or WFH.

Separating the W365 users from the application infrastructure should reduce the impact of this firewall scaling and random load changes.

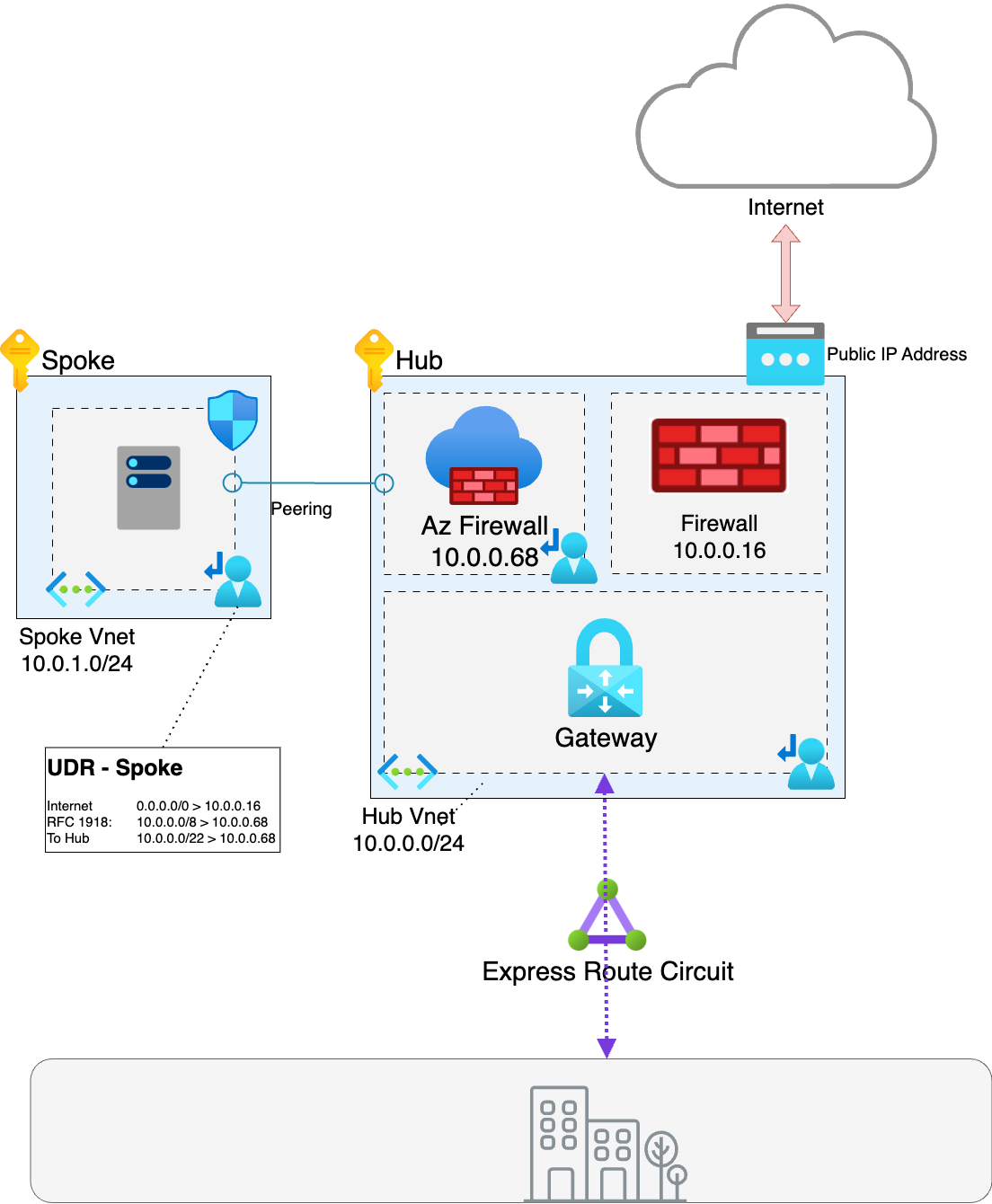

Option 2 - Split routing

This redesigns the Hub to include the Firewall NVA as well as the Azure Firewall, meaning that the Web/Azure Edge traffic does not actually pass through the Azure firewall, it goes directly to the Firewall NVA. Traffic is routed so that all RFC 1918 traffic routes to the Azure Firewall and all other traffic routes to the Firewall NVA.

Aside from the ability to identify the true source of the traffic this also reduces the load and traffic flowing across the Azure firewall which in turn reduces cost. This is particularly pertinent for Edge traffic as it means that traffic such as Telemetry and Azure Platform destined for Azure edge only passes across one firewall reducing the load on Azure Firewall and the traffic costs. The consequence of this design pattern is additional complexity of the UDRs but as long as this is worked out correctly and included in code it should not be too much of a issue in my view.

As always feel free to comment and hit me up with any feedback!